Decoding the ocean’s carbon cycle from dissolved oxygen variations

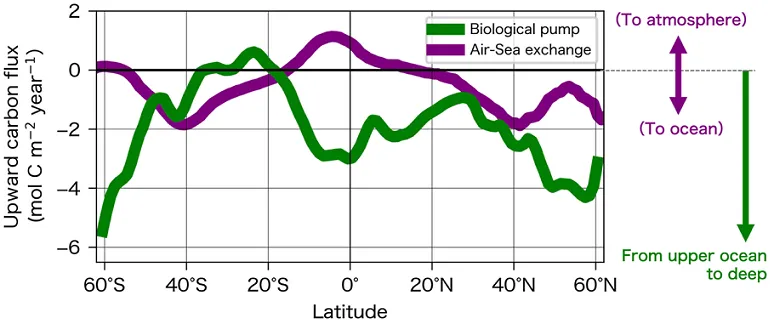

The ocean plays a vital role in shaping Earth’s climate by absorbing carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere and storing it for long time period (Fig. 1, left). One of the key mechanisms behind this process is the biological carbon pump—a system driven by several biological processes in the upper ocean (Fig. 1, right). In this process, dissolved CO₂ in seawater is converted into organic matter through photosynthesis by phytoplankton. Some of this organic material sinks into deeper layers of the ocean as carcass and feces, effectively transporting carbon from the surface to the depths. However, directly measuring all the pathways of carbon transport in the biological carbon pump is extremely challenging. As a result, scientists still do not fully understand where and how much CO₂ is actually taken up and stored in the ocean through this process.

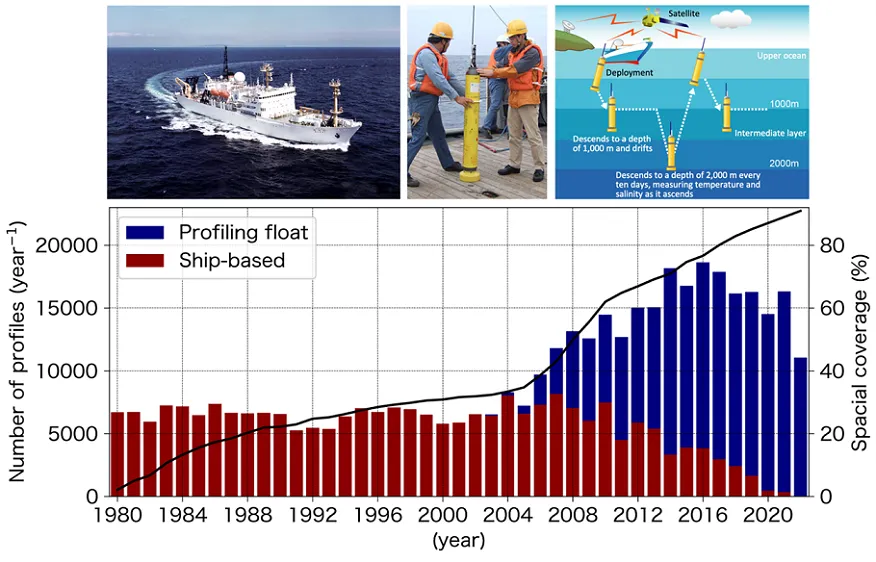

To tackle this problem, our study used a different approach. Instead of directly observing the carbon flux, we analyzed the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration in seawater, for which much more data are available (Fig. 2). During photosynthesis in the upper ocean, phytoplankton produce oxygen in nearly the same proportion as the amount of CO₂ they consume. Therefore, if we can estimate the net annual biological oxygen production from DO data, we can infer how much organic carbon was produced during the same period.

Dissolved oxygen in the surface ocean, however, is influenced not only by biological processes but also by physical processes such as air–sea gas exchange, ocean currents (horizontal and vertical advection), and mixing or diffusion (Fig. 3, center). In this study, we utilized over 400,000 DO observational profiles (Fig. 2) together with the latest knowledge and datasets on physical ocean processes. By quantitatively accounting for all these physical contributions, we were able to isolate the biological component of oxygen variation. This allowed us to estimate, for the first time, the net annual oxygen production by biological activity across the entire global ocean (Fig. 3).

When converted into carbon units, the global ocean carbon uptake via the biological carbon pump was found to be 7.4 ± 2.1 billion tons of carbon per year, significantly lower than previous estimates of about 13 billion tons of carbon per year. Moreover, the global distribution we obtained for the first time revealed that the biological carbon pump plays a particularly important role in carbon uptake in high-latitude and tropical regions (Fig. 4).

Looking ahead, by further refining this method and combining it with new ocean observations planned around Japan under the Habitable Japan program, we aim to deepen our understanding of material and carbon cycles in the surrounding seas.

For more details:

Yamaguchi, R., S. Kouketsu, N. Kosugi, and M. Ishii (2024): Global upper ocean dissolved oxygen budget for constraining the biological carbon pump. Communications Earth & Environment, 5, 732, doi:10.1038/s43247-024-01886-7.

(Ryohei Yamaguchi@A01-1, ECHOES. November 2025)